The Text, the Shastra, is not the book.

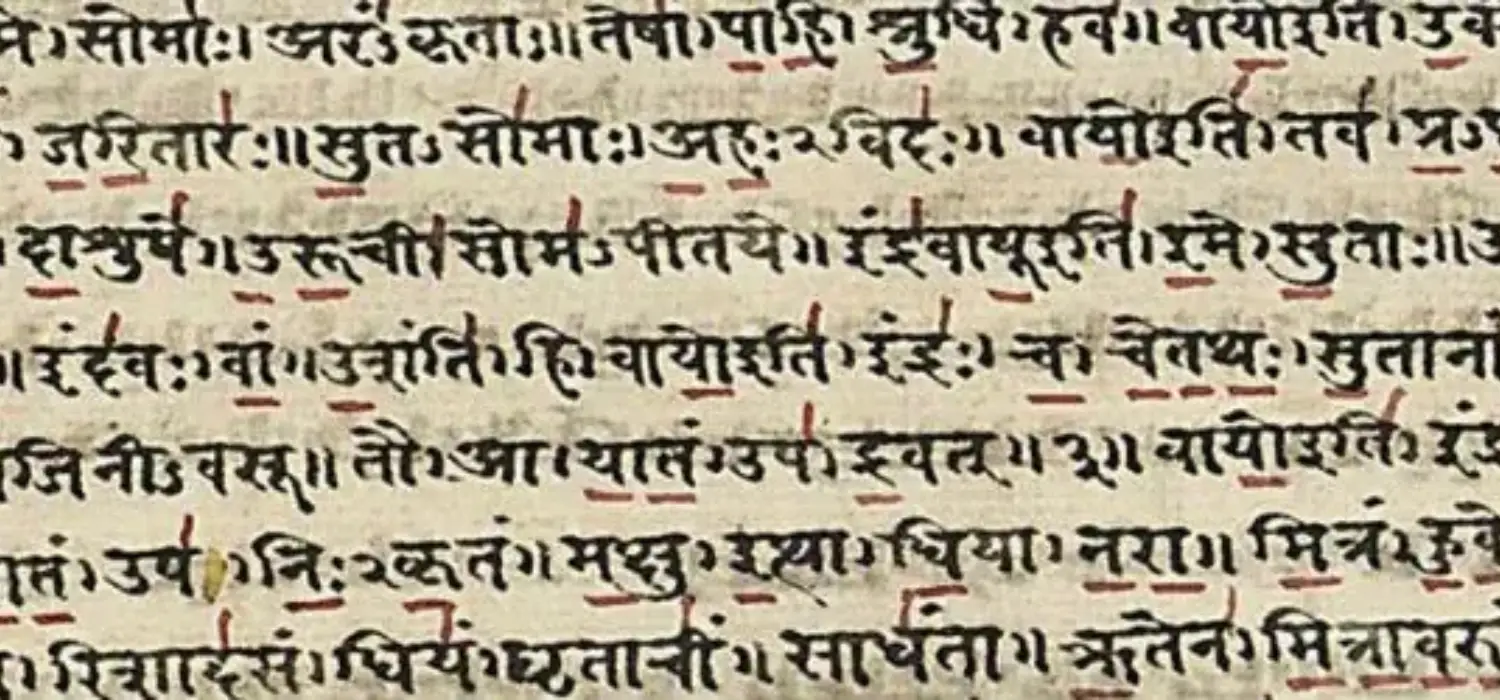

A text is not necessarily “a book,” and in an oral tradition, a text’s role is only a part of that tradition, one of its bodily limbs. In my engagement with an oral tradition over 45 years, I have seen very few written or printed texts, the main one being “

pushpanjalis” or privately published collections of

stotras and

shlokas used for

aratis, bhajans, and common pujas. There are various versions available (privately) and are often rife with mistakes. They reference other texts, such as

Vedas, Upanishads, Shankara, etc., texts that have never been seen in their totality or completion in a written form by most of us in the tradition of 52 lineages. Some of my gurus were able to “pull” whole sections of texts “from the sky” as it were, as if it were only coming from their memories. Whereas the mantras themselves, the sacred articulations, whose meanings must be considered in a whole different way than either common speech, or even symbolical or allegorical speech, remain fixed, but any doctrine or even ritual lays squarely in local mouths, in our case the discourse among the current generation of gurus in a particular tradition, only very weakly argued from the point of view of interpreting a particular text.

I am saying that the text is not nearly as important to the oral tradition as to the literate tradition. The text is not the guru, nor vice versa.

Largely because of my birth and upbringing in the West, I, also, have a burning curiosity for the text, and so, I have also spent my life searching for texts and reading them. I have also studied printed texts with traditional pandits in Sanskrit and Hindi in India, and I can tell you that even the pandits didn’t hold the text in the esteem that people in the West, or Western influenced people do. And this is regarding relevant, authentic, texts in Sanskrit. And even they would have the odd “mistake” – at least according to a reasonable interpretation of Panini’s “rules of grammar.”

I am certainly delighted, stimulated, and entertained by picking and choosing among a consumer’s paradise of available published texts, and reading the result of someone’s hard, often very disciplined work. It also makes it possible to be eclectic and innovative in one’s approach and work.

So we must be aware of that, and be able to identify it when we see it. And when we do, we must then be able to distinguish between the singer and the song.

A text is not necessarily “a book,” and in an oral tradition, a text’s role is only a part of that tradition, one of its bodily limbs. In my engagement with an oral tradition over 45 years, I have seen very few written or printed texts, the main one being “pushpanjalis” or privately published collections of stotras and shlokas used for aratis, bhajans, and common pujas. There are various versions available (privately) and are often rife with mistakes. They reference other texts, such as Vedas, Upanishads, Shankara, etc., texts that have never been seen in their totality or completion in a written form by most of us in the tradition of 52 lineages. Some of my gurus were able to “pull” whole sections of texts “from the sky” as it were, as if it were only coming from their memories. Whereas the mantras themselves, the sacred articulations, whose meanings must be considered in a whole different way than either common speech, or even symbolical or allegorical speech, remain fixed, but any doctrine or even ritual lays squarely in local mouths, in our case the discourse among the current generation of gurus in a particular tradition, only very weakly argued from the point of view of interpreting a particular text.

I am saying that the text is not nearly as important to the oral tradition as to the literate tradition. The text is not the guru, nor vice versa.

Largely because of my birth and upbringing in the West, I, also, have a burning curiosity for the text, and so, I have also spent my life searching for texts and reading them. I have also studied printed texts with traditional pandits in Sanskrit and Hindi in India, and I can tell you that even the pandits didn’t hold the text in the esteem that people in the West, or Western influenced people do. And this is regarding relevant, authentic, texts in Sanskrit. And even they would have the odd “mistake” – at least according to a reasonable interpretation of Panini’s “rules of grammar.”

I am certainly delighted, stimulated, and entertained by picking and choosing among a consumer’s paradise of available published texts, and reading the result of someone’s hard, often very disciplined work. It also makes it possible to be eclectic and innovative in one’s approach and work.

So we must be aware of that, and be able to identify it when we see it. And when we do, we must then be able to distinguish between the singer and the song.

A text is not necessarily “a book,” and in an oral tradition, a text’s role is only a part of that tradition, one of its bodily limbs. In my engagement with an oral tradition over 45 years, I have seen very few written or printed texts, the main one being “pushpanjalis” or privately published collections of stotras and shlokas used for aratis, bhajans, and common pujas. There are various versions available (privately) and are often rife with mistakes. They reference other texts, such as Vedas, Upanishads, Shankara, etc., texts that have never been seen in their totality or completion in a written form by most of us in the tradition of 52 lineages. Some of my gurus were able to “pull” whole sections of texts “from the sky” as it were, as if it were only coming from their memories. Whereas the mantras themselves, the sacred articulations, whose meanings must be considered in a whole different way than either common speech, or even symbolical or allegorical speech, remain fixed, but any doctrine or even ritual lays squarely in local mouths, in our case the discourse among the current generation of gurus in a particular tradition, only very weakly argued from the point of view of interpreting a particular text.

I am saying that the text is not nearly as important to the oral tradition as to the literate tradition. The text is not the guru, nor vice versa.

Largely because of my birth and upbringing in the West, I, also, have a burning curiosity for the text, and so, I have also spent my life searching for texts and reading them. I have also studied printed texts with traditional pandits in Sanskrit and Hindi in India, and I can tell you that even the pandits didn’t hold the text in the esteem that people in the West, or Western influenced people do. And this is regarding relevant, authentic, texts in Sanskrit. And even they would have the odd “mistake” – at least according to a reasonable interpretation of Panini’s “rules of grammar.”

I am certainly delighted, stimulated, and entertained by picking and choosing among a consumer’s paradise of available published texts, and reading the result of someone’s hard, often very disciplined work. It also makes it possible to be eclectic and innovative in one’s approach and work.

So we must be aware of that, and be able to identify it when we see it. And when we do, we must then be able to distinguish between the singer and the song.